By Emma Bastin

Picture yourself in the last shopping centre or high street you visited. One of the images which probably immediately springs to mind is that of the large windows of the shops, artfully filled with a select number of goods, designed to entice you into the shop and make a purchase. Today, window dressing and visual merchandising is a multi-million pound sector, employing designers, artists, and psychologists, but one hundred years ago, shop owners often simply piled their windows high with stock. Many believed that showing as many items as possible was desirable, so that the shopper would know that the shop sold exactly what they wanted or needed. But a revolution was on the horizon.

Changes to the way goods were shown in windows had begun in America prior to the First World War, and after the war, many mainland European retailers began to copy some of the ideas seen in the United States. American department stores had begun to use “open” displays, which showed a smaller range of goods in a more considered manner. The aim was to invite shoppers into the store to explore further. In Europe, these “open” forms of display were combined with artistic developments, and window dressing became a “craze”, with displays showing many facets of Art Deco design.1

The earliest British stores to take note of the developments happening overseas were London boutiques in the West End. Their high-end stock and methods of selling leant themselves to showing just one or two items in the window, but department stores windows also began to show a “dignified simplicity” which moved away from the stock-filled windows of previous eras. “Don’t overcrowd the window” became “battle cry” of display men (and increasingly, women), with far fewer items of stock in the window, better lighting and items arranged in groups on units and stands.2 Head Office at the progressive retailer Marks and Spencer Ltd also realised what a valuable advertising aid their windows were, calling them “the mirror of the store”. Although they did not tell individual stores what to put in their window displays they did decree that “window is not properly dressed if it looks as though heap of goods has been thrown into it. Merely to fill a window is not to dress it.” 3 The importance of this modern, clean look is demonstrated in the fact that the header for the Weekly Bulletin sent to each store is an clean-lined, Art Deco building, complete with large glass windows and an organised display within.

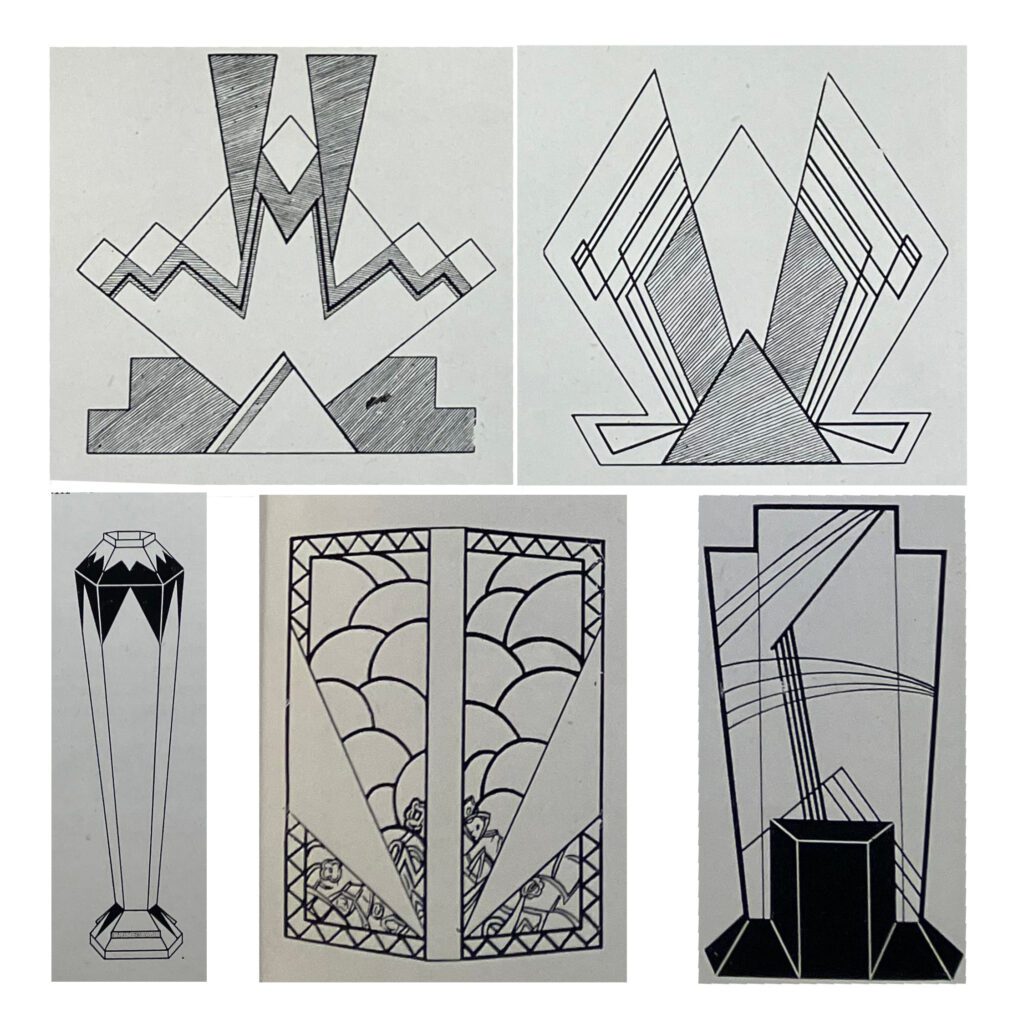

An early example of modern window dressing was at C&A Modes on Oxford Street in 1928. This was deemed “an interesting departure from traditional display” and it earned the store a full page write up in a trade journal.4 The store benefitted from some of the largest windows in London, and the result was deemed to be “extraordinarily striking and pleasing”.5 The image below shows the window in question: to our eyes it still looks busy, but this was a remarkably stripped back display for the time! The trade journal also includes some of the designs which had been use on backgrounds and on various display units, many of which embody Art Deco style.

Prior to the interwar period, window dressing had largely been undertaken by general assistants, with occasional interventions from the stock buyers, who wanted to ensure their goods had the best position in the window. By the 1930s, window dressing was becoming a profession in its own right: it was seen as a particularly suitable job for females, as women did most of the nation’s shopping, and because it relied on artistic skills. Shop fittings and display may have been modernising, but attitudes to gender certainly were not! Window dressers were required to maintain a delicate balance between creative expression, and commercial interests. Contemporary commentators said that a good display “can set the town talking”, and would be “talked about in thousands of homes”, but the most important object was to get passersby to enter the shop to make a purchase.6 To encourage a better standard of window dressing, prizes were awarded by newspapers such as The Daily Mail, which awarded Chamberlin’s of Norwich its top prize for a display in 1936 (see below).

Specialist companies offered whole ranges of stands, units and mannequins which could be used to display wares to their best advantage. Large sums of money were invested in structural changes to shop fronts and the buying of window-dressing equipment. The example below shows how in just two weeks, Brights, a store in Bournemouth was given a completely new, up-to-date look. The heavy wooden windows have given way to large, slim-framed panes, and an island window allows shoppers to view articles from all angles. The style of window dressing has also had an overhaul – overcrowded stock is now given space, and the mannequins present more realistic effect: it was no wonder that these modern stores were seen as “gleaming palaces”.7

European window dressing had made extensive use of metal and metal effects, and this crossed the Channel to Britain. For example, George Parnall & Co made shop fronts and fittings in “bronze and other metals”. It was also noted that stainless steel tubing, bakelite, and glass were being used, materials strongly associated with the Art Deco movement. Another “modernistic” approach was the use of “cellulosed paint”, which allowed backdrops to be repainted and redesigned relatively easily and quickly.8 When we look at black and white images of interwar shops today, it is hard to imagine what they would have been like when seen in full colour. Hilda Gibson noted in her book The Art of Draping that “colour was a useful ally”, and the way in which colour affected consumers was beginning to be investigated by early psychologists, and be reported on in retail trade journals.

This modern form of window dressing was not without its detractors: one trade journal scoffed that “much nonsense has been written – and done – with so called “modernistic” display [but] there is no special virtue in playing at kindergarten with stock.”9 Nevertheless, it clearly captured the public’s imagination and encouraged sales: windows packed to the rafters with goods were relegated to history. The legacy of these modern, Art Deco displays are evident every time we visit the high street as shown in the image below, showing a recent window at a Zara store.

If you’d like to find out more about the history of retailing, then I highly recommend Tessa Boase’s London’s Lost Department Stores, which is full of images and introductions to some of Britain’s largest department stores. She also gave a fascinating talk for the Art Deco Society that you can watch back on our Vimeo channel.

The Marks and Spencer Company Archive is also an excellent resource: you can find it at https://archive.marksandspencer.com/ and they have recently launched a digital archive.